In 2009, as Satoshi Nakamoto was launching the peer to peer cash system bitcoin, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences was awarding the Nobel Prize for Economics to Elinor Ostrom for her pioneering studies on how commons resources can be sustained through decentralized institutions that underlie economic activity. These apparently unrelated events may hold the key to ensuring the sustainability of our planet’s commons. But before we explain why, let’s define what the commons are and why sustaining them is important.

What Are The Commons?

In his article, The Common Good, Jonathan Rowe refers to the commons as “the realm of life that is distinct from both the market and the state and is the shared heritage of us all.” Wikipedia defines the commons as “the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society.” There are many kinds, including:

Ecological Commons (e.g. – air, water bodies, wetlands, landfills)

Civic Commons (e.g. – public spaces, public schools, public transit)

Social Commons (e.g. – caring for the sick, elderly & children; housework)

Cultural Commons (e.g. – literature, music, arts, design, film, video, television, radio)

Knowledge Commons (e.g. – intellectual information and content)

Collaborative Commons (e.g. – connected renewable energy internet, a new socioeconomic model for decentralized collaboration and value creation)

Why Is Sustaining The Commons Important?

The ecological commons play a crucial role in sustaining our existence as the earth’s ecosystems provide food, water, energy, medicines and building products. The social commons are an unrecognized and undervalued prerequisite for our economic systems to function. The civic commons play a critical role in building community wealth by strengthening the social networks in communities 1 while the knowledge commons represent our collective ability to solve complex problems. Lastly, we will introduce the concept of the collaborative commons, which is an emerging model for peer to peer collaboration and value creation.

The challenge in sustaining these commons was famously termed the Tragedy of the Commons 2 by Garrett Hardin. He used a hypothetical example of the effects of unregulated grazing on common land to illustrate how self-interested individuals acting independently do things that inadvertently exhaust or degrade the commons. As Sustainable Business Council co-founder David Browen put it, “it’s hard to ensure we don’t over farm the land, don’t over fish the seas, don’t over cut the forests and don’t take too much water from our rivers and aquifers.” 3 Lastly, this challenge is poignantly summarized by social activist Livien Soete in his article Economics As If Future Generations Mattered.

“One of the key barriers to taking action on the paramount issues of our time is that these problems are the end result of entrenched cultural, economic and social systems. Yet growing numbers of people are waking up to the reemerging Commons ethic, which holds that human systems must be aligned to match ecological ones. People believe that future generations have the inalienable right to a healthy planet.” 4

Our Economic Systems Don’t Incent Protecting The Commons

Our predominant economic systems have evolved out of the basic need for individual survival, safety and prosperity. As a result, these systems lack ways to incent individuals to make contributions to the long-term sustainability of the commons when there is no obvious or immediate individual benefit. Instead, a person contributing to the commons incurs the cost of doing so, and only benefits from those efforts when they access the commons in the future. And because the commons are also public and shared, any positive impact of his/her contributions will be overshadowed when most people are inadvertently harming them. This individual-centric dilemma is summarized succinctly by author and water conservationist Maude Barlow.

“Quite simply, to feed the increasing demands of our consumer-based system, humans have seen nature as a great resource for our personal convenience and profit, not as a living ecosystem from which all life springs. So, we have built our economic and development policies based on a human-centric model and assumed either that nature would never fail to provide or that, where it does fail, technology will save the day.” 5

The water commons, for whose preservation Barlow has spent her life advocating, is a good example of how our individual-centric economic model struggles to incent commons preservation. In 2000, the National Water Quality Inventory reported that agricultural pollution was the leading source of water quality impacts on surveyed rivers and lakes, the second largest source of impairments to wetlands, and a major contributor to contamination of surveyed estuaries and ground water 6. Yet organic farming, which has been demonstrated to support the health of watersheds 7 by limiting the amount of harmful sediments (soil erosion), nutrients (fertilizer, manure) and contaminants (pesticides) entering our water commons, still lacks widespread adoption by farmers because economic incentives are not sufficient to incent individuals to farm in ways that preserve the water commons.

Preserving the commons has largely been attempted through a combination of regulation, privatization, non-profit initiatives or socially conscious enterprises. Each of these areas has challenges.

- Regulation, which restricts commons access to ensure long-term preservation, can be overly complex, costly to enforce and hamper economic growth.

- Privatization, which grants commons ownership rights on the premise that individuals will take greater care in protecting assets they own, can also lead to short term profit maximization over long term commons preservation.

- Non-profits are overly dependent upon taxpayer funding and donations.

- Social enterprises, which essentially charge a price premium that could be considered a donation to commons preservation, struggle to compete against cheaper conventional alternatives.

All of these solutions are based on the assumption that people will act according to self-interests when accessing the commons. What if, however, our systems incorporated individual and collective interests? How might we create a system where caring for self was synonymous with caring for the commons? The missing incentive that ties caring for one’s self to caring for the collective is the true tragedy of the commons.

Aligning Social And Economic Systems For A Healthy Planet

Let’s return to 2009 and the work of Ostrom and Nakamoto. It turns out, their work was a watershed moment for our ability to align social and economic systems. Ostrom’s work proved that given proper incentives and circumstances, communities are capable of sustaining common resource pools. This contradicted the long-standing tragedy of commons belief that people interacting with the commons always maximize individual benefits. What Ostrom found was that people will cooperate to preserve the commons when livelihoods are directly tied to commons resources, like the 5,400 small businesses and 35,000 jobs of the Maine lobster industry. While Ostrom proved that cooperative commons preservation is possible, unless one’s livelihood depends directly on a commons resource, the individual incentive and effort required to sustain the commons typically outweighs the lack of immediate individual benefit. Now, we could argue that our collective lives do indeed depend directly on the preservation of our natural resource commons, but the problem is complicated in that a deed to preserve the commons, whose benefit often accrues to future generations, is not well incentivized in our current economic paradigm. The challenge becomes how to economically incent people to preserve the commons when their livelihoods do not depend on them.

Satoshi Nakamoto’s work included launching the cryptocurrency bitcoin and devising the first blockchain.[2] The bitcoin system, which manages peer to peer monetary transactions without requiring a bank, is the first system to economically incent individuals to cooperate to maintain a decentralized network without third party governance, regulation or privatization. In creating the blockchain, Nakamoto essentially created an automated system that incents individuals to cooperate globally to maintain a commons for managing digital money. The blockchain and similar distributed ledger technologies have rapidly evolved to enable communities to define the purpose and meaning associated with the digital money (or tokens of value) they manage. Thus, purpose-driven communities can mint, distribute and govern tokens that incentivize individuals to advance the community’s purpose.

The confluence of these two apparently unrelated events (Ostrom’s Nobel prize and Nakamoto’s blockchain innovation) represents the possibility to create a new socioeconomic model for global commons preservation. Ostrom pulled together a wealth of evidence and principles for designing successful commons preserving communities and Nakamoto sparked a technology industry that can be leveraged to enforce Ostrom’s design principles globally. Not only can people whose livelihoods depend on the commons organize to preserve them, but so too could people who simply want to make their living sustaining them. Caring for the commons can become synonymous with caring for one’s self.

A Blockchain Socioeconomic Model For Commons Preservation

This section introduces a decentralized community management model that can be used for commons preservation where individual incentives are aligned with collective interests. Note that this model itself is a commons. For clarity, we are describing a collaborative commons whose purpose is to preserve and restore other commons 8. The general idea is that blockchain could provide new tools and incentives for self-organizing communities that produce outcomes like a corporation but without authoritative leaders. Like the internet, a blockchain can have an application and protocol layer. The application layer is the main human interface while the protocol layer standardizes the communication functions of the network and ensures that it runs efficiently and securely. We will focus on the application layer, and defer the interested reader to this detailed document with protocol and application layer considerations.

The application layer provides the tools for decentralized communities to organize around a common purpose. While you can envision how a corporation organizes and operates with contracts, managers, and salaries for incentives, a leaderless community working on projects that contribute to a common goal is harder to imagine. To illustrate, we will discuss what these organizations would look like, how they would run, and how they could change the incentives around sustaining the commons.

What would these organizations look like?

These organizations have three distinct sub-groups, each with separate responsibilities, depicted in the figure below.

- For Benefit Common (FBC): This group determines the community’s vision, goals, and establishes guidelines and incentives for achieving them. It sets operational rules like how members come to consensus, how voting rights are earned, and how to manage funds to best reach its goals. This group governs executive type decisions and sets strategy. The FBC is launched when a group decides to start a community, and those founding members set genesis governance rules like FBC membership requirements and processes to change rules.

- Production Common (PC): This group is comprised of the people working on projects that align with the FBC’s stated goals. Contributions are tracked in a community accounting system (explained further in the next section) and rewarded with tokens. Contributors specify what type of token they would like to earn. Community, utility, or reputation tokens may be earned for contributions, the latter two enabling participants to earn rewards for providing services that keep the decentralized network running. Community tokens are defined by the FBC within the application layer, and would be exchangeable for other goods or tokens. Choosing which token(s) to accept as reward would depend on token valuation, desired use, expected future behavior and liquidity, as well as personal preference.

- Entrepreneurial Common (EC): This group interfaces with other organizations or communities. When the PC creates goods & services to sell, the EC sells them within or outside the community. The revenue is sent to each contributor proportional to their tracked contributions, and any revenue earmarked by the FBC for community investment goes to its wallet to be distributed to the PC in a way that best accomplishes the FBC’s goals.

Although these are three distinct sub-groups, a community member could be part of any combination of the three by meeting membership criteria. FBC membership requirements could vary among commons preserving communities, but membership in the EC and PC would ideally be open to encourage as much positive contribution to the commons as possible. The community is not owned by anybody, not even the founders, and therefore changes over time as participants change community operating rules and goals. Finally, the simple metaphor of running a lemonade stand illustrates the functions of these subgroups.

The FBC makes the house rules. If the kids follow them, their parents allow them to make lemonade to earn money from the stand. The PC is comprised of the people who buy groceries and make lemonade. The EC is the lemonade stand at the curb selling to neighbors, sharing the proceeds with the grocery shopper and drink maker. Finally, the house’s foundation, which goes unnoticed unless it fails, is the blockchain protocol that the entire lemonade stand business rests upon.

How would these organizations run?

These three sub-groups function collectively as an open value network (OVN), which is best described as “people creating value together, by contributing work, money and goods, and sharing the income,” a “framework for many-to-many innovation” and a “model for commons-based peer production” 9. These decentralized networks center around projects and open value accounting.

Any community member can start a project by defining a scope, estimating the project’s impact 10, and establishing the work to be done via workflow recipes 11 that serve as a pattern of activities (a recipe, a script) designed to simplify repeatable project setup. Because members are rewarded for their contributions in tokens, the project also specifies actions that merit reward, as well as something referred to as a value equation. Project participants must come to consensus on the value equation which states each contribution type’s value relative to the others. For example, an innovative idea could be worth twice as much as documentation, determining the split of value earned by the innovator versus the writer, and 5% is mandated to go back to the FBC to fund other projects. Once a person logs their contributions and they are verified 12, the contributor’s digital identity 13 would hold their claim rights to future revenue from that project, or any other project that builds on top of it.

To ensure each project aligns with the FBC’s goals, an additional approval vote in the FBC must take place. Here, it would make sense for votes to be optionally delegated so that trusted subject matter experts can vote for those who lack technical expertise to estimate the project’s impact. In addition to the ability to delegate votes, it will be important that available data related to measuring impact is open and equally available to all voting members, facilitating informed decisions.

All active projects are then listed on a marketplace where they can be discovered and requested to join by any PC member. Different types of projects could exist related to stewarding a commons. Ongoing projects with no “done” criteria could reward repeatable actions with impact like cleaning garbage out of a stream. On the other hand, finite scope projects would be similar to a software project where a team assembles to create a deliverable with done criteria.

Knowledge and assets created through projects are then listed in an asset & resource registry, which can be searched and accessed by any PC member. Any existing assets or resources included in a project then earn a portion of the project revenue. This creates value provenance where contributions are tracked and rewarded all the way back to original innovators 14. In addition, a decentralized commons marketplace (DCM) facilitates exchange of goods and services between members, paid for in any other type of environment asset (tokens, goods, services). This gives the community an opportunity to exchange amongst themselves, using self-defined marketplace rules determined by the FBC, before having to look to external, competitive marketplaces.

One final consideration to mention is that most community processes require staking. This means that a member must escrow a certain number of tokens, depending on the task, like a security deposit to get permission to do something. Sometimes the tasks that require staking also provide a reward for successful completion and return the stake, other times the stake is simply returned if no rules are violated. Example tasks include starting a project, voting, or listing a resource for community access like a garage. Staking is an incentive structure beyond project token rewards that punishes malicious behavior and can further reward positive behavior. Taking the stake from members who violate community rules prevents members from acting against the community’s purpose with no punishment. So, while extrinsic incentives are earned for sustaining the commons, a member is also incented to act in the best interest of the community or else lose their stake as punishment.

How would this change the incentives around the commons?

This community structure allows people who contribute to the commons and earn tokens for doing so. Because the goal is to align individual incentives with collective interest, the tokens need to provide for individual needs. This means that reducing runoff into a local stream could be your career, and so could removing plastic from the ocean. To meet this need, tokens should be designed as a currency to use in exchange for goods and services, or to provide blockchain protocol layer services 15. This is the lynchpin of the incentive model. The tokens earned must maintain value like a currency so that they are exchanged for things like food, shelter, leisure, or investment opportunities. Achieving these characteristics is mostly determined by monetary and fiscal policy, which will not be defined in this article but is the next step in designing the token model 16.

In addition, there remains the question of where the rewards come from when the projects do not produce something to sell, as is the case of planting a tree on a stream bank. In an effort to change the existing paradigm of commons preservation where social impact organizations are dependent on external funding, the tokens need to come from within the community. Project rewards would come from tokens minted within the community that are only earned with proof of impactful work17. The work done to increase the health of a commons backs the tokens. These tokens would require a high level of member confidence in their exchange value. The primary mode of determining its exchange value would be through supply and demand for impactful work related to specific commons.

Supply and demand would be created by incorporating the contribution log into the token’s data, essentially recording the value’s provenance. Contribution logs would be categorized by the commons they supported. With that information embedded into each token, people looking to exchange would be asked to set blockchain wallet preferences so that when given the option, coins earned from their preferred value type are accepted first in exchange. For example, Sally and Ben both want to buy an apple. Jim sells apples, and prefers water tokens. Sally has water tokens, and Ben has art tokens. Sally’s exchange goes through first, and because all apple farmers prefer water tokens, she only needs to spend 1 token for an apple, but Ben has to spend 3. This would create demand for specific types of tokens, increase their value, and incent contributions to the commons that people value most or feel are the most important to preserve.

Example Scenarios For the Water Commons Community

This model would need to work alongside existing careers, organizations, and economies. The illustrations below show how people would interact with this model if it existed today. We then conclude by presenting a simple, non-monetary action that can be taken to help test the idea.

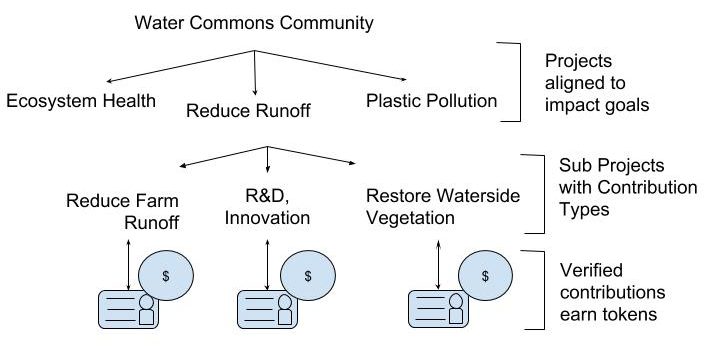

For the scenarios, imagine that a community forms with an impact goal of protecting the water commons. The figure shows the community’s structure around impact goals, projects, and contributors. The impact goals could include things like improving aquatic ecosystem health, reducing nutrient runoff and preventing plastic pollution. Each of these major impact goals would have projects under it with defined contributions meritorious of tokens. The figure includes the examples of reducing farm runoff, researching new solutions, or restoring waterside vegetation. Anybody working on those projects will accrue tokens in their digital wallet proportional to their contributions.

Six scenarios below explain in further detail different ways that you could contribute to the water commons community.

Change Existing Business or Organizational Practices

There is an existing project to reduce the annual rate of nitrogen runoff in a watershed, and businesses like farms are encouraged to submit their nitrogen reduction contributions. Suppose you are a farmer working near a river, and decide to try organic farming. Rather than using man-made nitrogen fertilizers, you use compost. The project clearly states that reducing nitrogen runoff by 1 lb = claim to 10 tokens. The project is active every year, but has a limited number of tokens so that once the runoff reduction goal is reached, no more can be earned within that year. You submit proof of your compost-as-fertilizer practices, and earn the respective tokens 18, which supplement your income. You can exchange them with the EC for EC tokens, which can in turn be exchanged for fiat currency. Otherwise, you could trade them for things that other community members are offering on the DCM.

Make Sustainable Purchases

A consumer prefers to buy organic groceries on the DCM, which were more expensive before the runoff projects. However, now that farmers have the opportunity to earn tokens for their organic practices, the number of organic farmers has increased, causing the supply of organic produce to increase and the price to drop, and you reliably choose the organic produce19. The consumer therefore does not need an additional incentive to buy organic because it is now more affordable. Consumers therefore do not need to interact with projects directly. The same argument holds for offering the products on the market outside of the commons20.

Be an Innovator and Find New Solutions

You are an innovator and believe there is a way to make nutrient runoff harmless to the ecosystem with a biological mesh. The FBC does not have an appropriate project to join, so you create a new one. You write a proposal that includes impact metrics, targets, and the value for a unit of impact. This project would be deliverable-based because it will contribute to the nitrogen runoff knowledge commons and have a defined end criteria.

You stake some tokens, submit the proposal, and wait for it to be approved by the FBC. Once approved, your stake is automatically refunded to your wallet, and other collaborators join the project. The next step is for the entire project team to come to consensus on actions that merit PC rewards and their relative values. Once this is done, project contributions can be tracked, and when the project completes the agreed upon value equation calculates the percent of future rewards or revenue each member earns.

The resulting innovation is then open on the DCM for anyone to access. When a farmer uses the knowledge to create other value, a portion gets shared with the innovation team for their quality work. When a community member buys mesh to reduce runoff, a certain portion of the price also gets distributed to the innovation team, along with the teams who would have to manufacture the mesh. These rewards automatically calculate, and the more useful the innovation, the more a project team can earn21.

Make a Career out of a Cause that Matters

You like to plant trees, and their root systems coincidentally filter nutrient runoff out of the water. You can earn water commons rewards for planting these trees. This requires an ongoing project which specifies planting trees near a waterway to be an action worthy of reward. Once set up, landowners in the watershed along stream banks submit a need for tree planting that is verified by the project’s automated verification system22. The system checks that the landowner indeed owns land within the watershed and it borders a waterway. The number of trees and type to be planted are then submitted by the landowner and appear on the project marketplace.

Since you enjoy planting trees, you join the project, along with a neighbor who grows saplings. He gives you the saplings, and you plant them based on the landowner’s request. Both you, the tree grower, and the landowner submit proof of contributions. You and the tree grower earn the number of tokens calculated by the value equation.

By sharing the reward among all contributing parties, participants will earn more if they make a higher impact for a lower cost, similar to our current economy. This will help optimize activities to use the fewest resources with the highest impact.

Verify Project Contributions and Earn Tokens

For a project contribution to trigger reward distributions, they must be verified. If not, people could falsely claim that they should earn tokens. The process requires verifiers. Suppose your neighbor planted a tree on a stream bank. As a landowner, you can verify that a tree has been planted by a specific individual. To prove this, you submit a stake to become a verifier, submit formal proof of the tree being planted by a specific individual, and earn a reward for doing so. If you submit dishonest proof and you are caught, you lose your stake, which is much larger than the reward you earn for honest verification. In the end, you end up with a higher property value because of the trees, healthier local ecosystems, and token rewards for verification.

Help Define and Measure Impact for a Commons

The FBC determines impact goals, and ways to measure impact. Social impact organizations and subject matter experts will generally be most qualified in impact tracking and measurement. They are instrumental in evaluating and proposing a way to measure the FBC’s goals.

As a scientist, you submit the requisite staking tokens and a proposal on how to measure impact to the FBC. Other scientists and organizations could submit their proposals, and the FBC votes on the best one. If you submitted the winning proposal(s), you earn token rewards as the framework is successfully used. After a certain period of successful implementation, the stake is returned to the user, and is only taken as punishment if a proposal does not meet submission criteria, or meets the criteria of a bad framework, both specified by the FBC.

Next Considerations

This blockchain based solution to the general lack of individual or organizational incentives for stewarding the commons is our hypothesis. Testing it and our assumptions is the next step23. Once we confirm our assumptions and hypothesis, detailed work can ensue. Token monetary and fiscal policies need to be designed to create a currency. Legal considerations and political support are necessary for the public to trust that the token will be accepted for exchange, and blockchain’s feasibility to underpin global communities of value exchange must be tested. Notwithstanding these nontrivial challenges, we are excited because of the potential and number of other people working on similar ideas.

If you would like to support this idea, we need feedback to help test our most important assumption by answering this question: if you could make your job one of protecting or restoring a commons, would you? Send us a message or leave a comment.

Finally, we would like to recognize other thought leaders who have contributed to the challenge of sustaining the commons and new economic structures, helping us form our thinking through collaboration or other published work. This includes: Andreas Freund; Desmond McKenzie; Tiberius Brastaviceanu; Samer Hassan, David Rozas & Team; Simon de la Rouviere; Marc Ziade; Daniel Jeffries; and Elinor Ostrom.

Footnotes & References

- Reclaiming The Commons, CommunityWealth.org

- The Tragedy Of The Commons, Garrett Hardin

- The Tragedy of Privatizing the Commons, David Browden

- Economics As If Future Generations Mattered, Livien Soete

- Water As Commons: Only Fundamental Change Can Save Us, Maude Barlow

- Protecting Water Quality From Agricultural Runoff, EPA 841-F-05-001

- How Organic Farming Protects and Conserves Clean Water, Jean Nick

- Because this model is a commons, it is also vulnerable to extractive forces. While not within the scope of this paper, one can read more on ways to protect collaborative commons from competitive markets here.

- Open Value Networks

- To value an action, estimated impact measurement frameworks will be needed. These should be introduced to the community via staked proposals before a project is initiated, and the best impact measurement techniques proposed can be accepted and used in the PC. An interesting project exploring this area is called Regen Network.

- ValueNetwork.referata.com

- The verification process is done by staked members who earn a reward for verifying. It is analogous to the protocol layer utility services, but done at the app layer with simplified consensus processes.

- We assume that each actor has a unique digital identity that holds personal information and value, similar to a wallet.

- To avoid the situation of paying the inventor of the wheel forever, contribution values decay over time to represent the commoditization of innovation.

- These include things like transaction or contribution validation, and when performed, earn additional tokens as a reward for the service. These keep the protocol, and therefore the entire community, running.

- Clarity on the steps to designing a blockchain token model was gained thanks to Marc Ziade of ConsenSys defining a token development framework.

- created through verified contribution logs

- The value of the token reward needs to be high enough that it more than covers the additional cost of protecting the commons by reducing runoff.

- Assuming the market acts like a competitive market with respect to supply and demand of subtractable goods. In a decentralized DAO market, information symmetry is the only main difference between it and a competitive market.

- The difference between the two is the farmer could avoid some costs of distribution with blockchain technology, making atomistic trades technology mediated, rather than middleman mediated, and gives the farmer higher revenue from the same sale price.

- The difference between this and the farmer example is that the innovator, like most R&D teams and startups, incur higher risk because their reward relies on the use and implementation of the innovation. This should cause innovators to 1) work to make their work relevant and usable, but at the same time 2) leverage existing solutions as much as possible to avoid the risk of delayed, or no rewards. The book, “Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming,” is an excellent illustration of this point. It contains a portfolio of solutions that when put together, reduces atmospheric carbon dioxide to what scientists would consider to be a stable level. The majority of these solutions would actually generate revenue, growing the economy. Despite this combination of known solutions with a business case, research into reducing carbon dioxide emissions continues in competitive markets. However, in the DCM, implementing existing solutions has the incentive of sales revenue, as well as tokens rewards for contributing to the FBC’s goals.

- This would be a system of smart contracts that pull data from oracles to verify specific conditions and trigger subsequent actions.

- First and foremost is the assumption that creating rational economic incentives for stewarding the commons will increase the ecological and social health of our world.